An adult female Calabar Python 3'1" length, 630g weight, 2004.

A 2-month old neonate Calabar Python showing the typical red and brown

coloration.

The ruler in the picture is 6 1/2 inches in length.

(Updated January, 2010)

The Proposed U.S. Government

Python Ban: A Larger and Potentially Fatal Issue to the Hobby Left Unaddressed:

As I write this, the process to formulate a Bill to ban python importation is still ongoing and some sort of Congressional action may be coming soon. Given the recent apparent inability of Congress to investigate, evaluate facts and/or data, and arrive at reasonable solutions, I would be surprised if a Bill is passed that will come close to doing anything but anger both sides of the debate. The point I would like to make here is that in the midst of all of the "drama with the United States Association of Reptile Keepers actively pushing one viewpoint and the Humane Society of the United States pushing another, everyone is ignoring an issue that in my opinion may eventually do much, much greater damage to the hobby - the importation, maintenance, breeding and sale of highly venomous snakes.

The potential of venomous snakes to become established in many areas of the United States is a very real threat. Places that immediately come to mind include Florida (the center of reptile importation), the Gulf States, Texas, Western United States deserts, and large parts of the West Coast. I believe that this is a much greater threat than constrictors and it is currently being ignored by everyone - the hobby, the Public and Congress. A quick visit to the "kingsnake.com" classifieds indicates that for $2000, you can be the proud owner of a large collection of mambas, Death Adders, Terciopelos, Puff Adders, South American Rattlesnakes, Gaboon Vipers and spitting cobras. Some dealers do state that they will not sell these species to people living in areas that forbid keeping venomous reptiles. I did not, however, see any queries about potential buyers' prior experience with venomous reptiles! No questions as to the housing planned for these animals, the food supply, the size of the collection, or any other factor that would indicate sufficient knowledge to keep these animals safely! I believe that this existing situation is intolerable and may come back to haunt us all at some point in the future. I have spoken to former reptile owners who bought species with little or no negative information from the dealers, or downright mis-information - a sale is a sale, and let the buyer beware. So right now, we are ignoring a situation that could destroy our hobby. Having a 15-foot Burmese eat a small pet dog is bad enough, but having someone quickly die after being bitten by an introduced species of venomous snake could sufficiently panic the Public (and Congress) into enacting extraordinarily intrusive laws that will make maintaining snakes as difficult as maintaining hawks. How many deaths from mambas would have to occur in the Everglades for South Florida tourism to fall off? How many cobra bites in a Western U.S. National Park would have people avoiding trips there? Is there anyone who seriously thinks that such introductions are an impossibility? I would assume that anyone who cares about the future of our hobby will know that changes are needed and the best place for these changes lies in the behavior of dealers - not in Government laws. The exact nature of these changes will be the subject of considerable discussion, but if we do not acknowledge the difference between selling a Milksnake and selling a WC female mamba who may be gravid, there is an excellent chance that extremely unpleasant regulations will be forced upon us. When I first started this home page about 8 years ago, I warned about the continued sales of large constrictors and highly venomous reptiles. There are now three large constrictors established in South Florida and the hobby is scrambling to fight off Congressional Bills. The venomous reptiles are, as far we know, still not an issue. I would suggest that it be preemptively addressed, before public outrage and fear forces our hand.As of

today (1-9-11), there is a chance that we will see a ban on the

importation of

pythons, boas, anacondas etc. The ban may or may not include the

vast majority of boas and pythons that are much smaller. In my

opinion, either outcome

will have exactly the same impact on the ecological situation as not

passing

any bill at all - absolutely no impact. The animals are with us

and the

only question remaining is how much damage they will eventually do to

the environment,

and to the Public's perception of a hobby that involves breeding snakes

and

other reptiles. As far as the environment is concerned, there

will probably be

very weak data and very strong opinions. The "iguana

scenario" where a "pleasant animal" becomes established without

much impact on anything will be put forth by some while others will

advance the "brown tree

snake scenario" where an introduced snake species devastated Guam's

ecology. Most probably, the true impact

will not become evident until much later, and as I said above, the

snakes are already here and passing bills is a waste of time.

Addressing potential future issues while there is still time

would, in contrast, be a very constructive use of our energies.

GENERAL COMMENTS ABOUT THE PAST TWO YEARS:

I

have been keeping snakes for a long time - seriously for about 11 years. During that period of time I have had only

one or two animals die and, I confess, I took this as being the normal state in

a well-maintained collection. Well,

perhaps it is, perhaps I did things wrong during the last two years (things that I am unaware

of), perhaps something major is going on that I am unaware of, and perhaps the

"Law of Averages" finally caught up with me. 2008 began with 16 animals in my

collection and ended with 10 animals (including 2 added during 2007). A total of 8 animals died! There was no real pattern - I lost my

longest-term captives (1.1 WC Calabar Pythons); long-term CB animals (a 1.0

Mandarin Rat Snake and 1.1 Flame Snakes); and 3 recent WC additions, South

American Green Racers (1.1 Phylodryas baroni and 1.0 P. aestiva). The only animal where the cause of death was

obvious was the female Calabar who had an everted oviduct after laying a clutch

of four eggs. 2009 hasn't been much better and

I lost 1.1 Baja Mountain Kingsnakes, 1.1 Calabars, and 0.1 Mandarin

Ratsnakes so the collection is now down to 6 animals. I would add

that I have looked at records of longevity of snakes in captivity and

all of the animals with the exception of a male Calabar were well up

into the range where deaths have been recorded so I am wondering if the

deaths may not have been, at least partly, simply due

to age-related health issues. All in all, though, it has

been an

absolutely awful period for someone who was simply not used to losing

animals...

ABOUT MYSELF:

HERPETOCULTURE

AND CONSERVATION:

The

idea that herpetoculture could and should play a positive role in the conservation

of species has been advanced by a number of people within the hobby. This

is largely based on two factors - the possibility that animals maintained

within the hobby will form a repository of species that could, at some later

time, be introduced into the wild thereby increasing natural populations or

replacing those that have disappeared; and the reduction of collecting

pressures on existing populations through the increased use of captive born

animals. The validity of both of these ideas is, however, very much in

doubt. There are extraordinary difficulties involved in the introduction

of captive animals back into the wild. It is generally agreed that unless

essential precautions are taken over a long period of time, there is a very

real danger of introducing alien microbes into the environment along with the

target species. For example, my collection is housed in one room and

currently contains one wild caught species, the Calabar Python and the

remainder purchased at different times from different breeders. None of

the animals, either wild caught or captive born, have been kept in the type of

cages and/or room that provides fungal, bacterial, and/or viral

isolation. While I have made efforts to use disposable gloves while

cleaning cages and feeding, there have certainly been numerous lapses. It

is therefore probable that all the animals have been exposed to the complete

array of potential disease-causing organisms in the room. The possibility

does exist that the deaths that occurred in my group this past year resulted

from alien microbes attacking species with no natural immunity - or lacking

normal immunity due to long-term adverse health status due to the stress of

captivity. Currently, they are given clean water and parasite free food,

and do not face many of the natural stressors that wild populations have to

deal with. Such stresses in animals reintroduced into the wild may make

them susceptible to opportunistic pathogens they have been formerly exposed to

from other animals that were housed in the same room. More importantly,

releasing these animals back into the wild might allow some pathogen to invade

wild populations of these and other species with possibly devastating

results. A Chytrid fungus and various viruses have been proposed as key

contributors to the global decline of frogs. This follows an alarming

pattern of "emerging infectious diseases" (EIDs) that have affected a

diverse group of animals and plants globally. These pathogens may have

been spread into amphibian populations by tourists, or by the herpetologists

who were studying these animals. As travel becomes more accessible to

larger numbers of people, the global spread of disease causing entities becomes

more of a probability than a possibility - witness the spread of HIV.

Some years ago, I went to the Monte Verde Rain Forest

Preserve in Costa Rica. Until recently, the Preserve was home to the

Golden Toad (Bufo periglenes), which is now extinct due to fungal

infection, and is to be found only on T-shirts and hotel signs. On a

Tuesday morning I made a last check on my snakes, cleaned some cages, and

changed the water. That afternoon I flew to Costa Rica and spent the

night in San Jose. Wednesday morning a car was rented, and I was walking

in the rain forest by 4:00. A single day after I had been dealing with a

fair number of snake species, all of them exotic to Costa Rica, I was walking

through the Park and areas around it. At the sides of the roads in the

region, I would lift the occasional rock or turn a log looking for

snakes. Since I was very conscious of the possibility of my inadvertently

leaving unwelcome microbes in that environment, I had showered before the

flight and taken only clothes that had just been washed. It certainly

didn't reduce the threat to nil, but I felt that it was a prudent

precaution. I wonder, however, how many others (including herpetologists)

have done the same.

Even if we could take the

proper precautions and had animals that were isolated from other species, it

would still be very difficult to successfully introduce a species into the

wild. Long-term captivity and breeding programs result in populations of

animals that may be functionally and behaviorally different from wild

counterparts. Those of us active in the hobby know how easy it is to

breed for various color and pattern traits. At the same time, we are also

selecting for other far less obvious (or invisible) traits. Selective

breeding for prize winning German Shepherd show dogs resulted in the introduction

of hip dysplasia in the breed and there are numerous breeds known to be

associated with adverse health effects. By the very nature of the hobby,

we tend to select animals with large litter or clutch sizes - traits that may

prove to be a disadvantage for snakes in the wild. Similarly, we will

probably select for individuals that eat the food items we have access

to. It would not be surprising if, over time, the average captive Gray

Banded Kingsnake hatchling (Lampropeltis mexicana alterna) takes mouse

pups as first food much more readily than lizards, its usual initial

prey. This behavioral shift would simply reflect the decreased

reproductive potential for those animals that accept only live lizards as their

first food and/or are difficult feeders and therefore either fail to thrive or

do not achieve reproductive maturity as rapidly. Should a change of this

nature take place, it might not be accompanied by any morphological alteration,

and may be welcomed by the hobbyist – but the release of such animals into the

wild might result in total failure if their offspring are not equipped to

accept their normal initial food species.

Recent evidence has been published indicating that captive-reared salmon

raised in aquaculture farms do not survive as well when released into the wild

as do WC fish. The reasons for these

differences are not, as yet, known but it should be apparent that the same

traits that enable animals to survive in an aquaculture environment may be

detrimental when attempting to survive and breed in the natural environments.

THE COLLECTION

TODAY AND PICTURES OF ANIMALS THAT HAVE DIED DURING THE LAST TWO YEARS

(all animals CB):

Calabar Pythons (Calabaria (= Charina) reinhardti)

An adult female Calabar Python 3'1" length, 630g weight, 2004.

A 2-month old neonate Calabar Python showing the typical red and brown

coloration.

The ruler in the picture is 6 1/2 inches in length.

The Calabar Pythons are one of the first species

that

I kept and bred. I have described my experiences

with

the husbandry of these interesting animals in a Section below.

0.1 Mountain Kingsnakes (Lampropeltis zonata

agalma); 11/97

Baja Mountain Kingsnakes, 2006. Male above, female below.

The California Mountain Kingsnake is one of the more

attractive

Kingsnake tricolor species.

1.0 Brazilian Rainbow Boa (Epicrates cenchria

cenchria);

adult, 1/99

The iridescent Brazilian Rainbow Boa is certainly

one

of the most beautiful snakes. It is a fairly popular species

within

the hobby although I remain puzzled as to why it is not even more

commonly

kept. It is an ideal size, relatively easy to maintain, and not

difficult

to handle.

0.0 Flame snake (Oxyrhopus rhombifer inaequifasciatus); neonates, 5/00

June, 2006

Male (died)

Female (died)

Head of male

I was fortunate in being able to purchase two

hatchling

"Flame Snakes" in May, 2000 from Gulf Coast Reptiles in Naples,

FL.

They were part of a clutch of eight eggs laid by gravid female recently

imported from

Paraguay.

Using the keys to species and subspecies found in the "Catalogue of

Neotropical

Squamata; Part I. Snakes" by J.A. Peters and B. Orejas-Miranda (1970),

I determined

that the animals were Oxyrhopus rhombifer inaequifasciatus,a

subspecies

that is found in Paraguay. I have not located any pictures of

this

subspecies on the Internet so I am attaching three - a male, female,

and

head of the male. Note the different coloration between the

female and

the male, the latter having larger red areas dorsally. I have

only seen one

other specimen of this subspecies for sale and that animal was also a

male and was similar in coloration to mine. This species is

rear-fanged but I have

not

located any references to

human

envenomation. They took live mouse pups as first food and I have

continued

feeding them live mice. Based on the lack of coiling when being

handled, at first I assumed that they were not constrictors but I have

observed the male throwing very tight coils around a large

fuzzy prior to eating it so the issue is still undecided. I have

removed mouse pups from the jaws

of

the female and although there was ample evidence of a bite, the mice

have

not exhibited any obvious signs of toxicity. The snakes are are

extremely secretive and remain under the bedding (paper) almost

constantly, emerging only after the lights are out. As they have

matured, they have become less excitable and they have never shown

any

tendency to bite.

I have noted an interesting trait in

both animals. On April 16, 2004, the

female

had what appeared to be a swollen jaw. I checked the male and

discovered

that he too had this "swollen jaw". It appeared as

though

the animals had simply "puffed out" their lower jaw. The jaws

were

firmly closed (no gaping that would indicate any form of infection)

and

the swelling seemed to vary during the course of the day. Since

the

female

had eaten three fuzzies during the night (the male did not eat), I

decided to leave them alone and check them later. As it

turned

out, the "swelling" disappeared and the animals returned to normal

appearance

the next day:

I have noted this behavior additional times and the

swelling has become fairly constant in the female. In December of that year, I

noted that there was also a swelling in the lower part of the neck:

I took the animal to the University of North

Carolina

Veterinary Hospital where it was given a thorough examination by Dr.

Greg Lewbart and Mr. Larry S. Christian. Tissue samples and swabs

were taken and infections, fluid build-up, and solid masses were ruled

out. To date, the

animal's condition has not changed and she continues to eat so I am

simply keeping

track of her appearance and monitoring her weight.

Both animals grew rapidly

- from 6-8g. at

arrival

to approximately 235g. for the female and 300g. for the male at the time of his death. The

husbandry of the animals

are

identical to those I use for corn snakes (70-75°), paper bedding,

hide

box, and water bowl. They are currently housed together in

a 20-gallon

aquarium with plastic mesh tops. As is the case with all of my

aquaria, it has an insertable divider that enables me to track

the feeding of each animals separately. This year, the male

became infected and died with what appeared to be "blister disease" -

there were lesions on its ventrum. The female died some months later with no signs of "blister disease".

Oxyrhopus are being bred by several hobbyists in

Europe and a friend and I purchased two clutches this year. He

was attempting to get them to a sufficient size to be able to eat

new-born

pinkies and at one point he fed them frozen, locally caught, small

skinks. Immediately after that, they became sick and died.

Subsequently, additional neonates were purchased from the same

source and they are currently being converted from lizards (anoles

only!) to mice. I will take possession of animals as soon as they

are taking mice without any problem.

Mandarin Rat Snakes (Elaphe mandarina);

hatchling

- female.

Male Mandarin Rat Snake (deceased) - Picture of current male Mandarin will be coming

Female Mandarin Rat Snake (deceased).

The range of this species of rat snake is very

large and there is considerable variability in the animals coming onto the

market. The male of the pair I own with a friend died this year.

They differed considerably in appearance but we have not been able to learn

anything definite about their parental stocks and therefore do not know whether

this is normal "within-litter" variation, or whether these animals

represent geographical areas.

1.1 African Mole Snakes (Pseudaspis cana);

neonates,

4/04

Male African Mole Snake

1.1 Mussurana (Boiruna maculata); CB 12/06

I purchased a pair of CB Mussuranas this past year. This is a species that I have always wanted to keep. It is a large rear-fanged constrictor with several species and numerous subspecies ranging from Mexico well into South America. These animals have eaten well and have grown considerably in the time that I have had them. They arrived weighing 40+g. and after a year, currently weigh 90+g.

CARE OF CALABAR PYTHONS WITH NOTES ON BREEDING AND EGG INCUBATION:

During the last few years, requests for information about the husbandry of Calabar Pythons (Calabaria reinhardti) have reached me via my home page and subsequent e-mail. Given the apparent interest in Calabars, I have decided to put the following information here in the hope that it may be useful to people who wish to keep these animals.

Taxonomy: In 1993, the herpetologist A. G. Kluge studied the anatomy of this species and concluded that it was closely related to the Rosy Boa (Lichanura trivergitata) and the Rubber Boa (Charina bottae). This finding placed the Calabar Python in the boa subfamily, rather than that containing the pythons. He then combined ("lumped") the three species (Rosy Boa, Rubber Boa, and Calabar Python) into one genus, Charina. Other herpetologists have informed me that while Kluge's conclusion that C. reinhardti is a boa rather than a python is generally accepted, his proposed taxonomic changes are still somewhat controversial although some herpetologists have accepted them and consider the current name for the Calabar Python to be Charina reinhardti. I am not a herpetologist so my views about the purpose of taxonomy are a bit closer to those of the earlier taxonomists - that is, a central purpose of the Linnean classification scheme that was to make order out of the previously haphazard and imprecise way of naming species. The renaming of species that have had the same names for long periods of time may cause confusion, especially among people who aren't aware of the most recent taxonomic changes. An excellent example of the confusion that taxonomic changes can lead to was also generated by Kluge after he concluded that the common Boa (Boa constrictor) and two species of boas found in Madagascar should be placed in the same genus, Boa. The two Madagascar species were Dumeril's Boa (Acrantophis madagascarensis) and the Madagascar Tree Boa (Sanzinia madagascarensis). Here's the problem - since Kluge placed all three species in the genus Boa, he was left with both Madagascar species having the same name (Boa madagascarensis). There are only two ways to address this problem. The first is to change the name of one species entirely as follows:

Old

name

New (scientific)

name

Boa constrictor

Boa constrictor

Boa constrictor

Dumeril's Boa

Acrantophis madagascarensis

Boa madagascarensis

Madagascar Tree Boa Sanzinia

madagascarensis

Boa mandrita

This creates a new species name, Boa mandrita, that bears no

resemblance to its former name and is therefore rather confusing.

The second way to address this problem is to publish

the

paper with your findings but not change the names. The

information

about the evolutionary relationships will then be in the literature

where

interested people will become aware of it, and the silly confusion

caused

by this type of name change will be avoided. Whether

Kluge's findings with Calabaria

made it absolutely necessary to place this species in a new genus

rather than

allowing it to to retain its name (as a boa) is something that will

have

to be decided by herpetologist taxonomists. For now, I'll stick

with

the genus Calabaria. Regardless of the fate of the

scientific

name changes I will, of course, continue to use the common name,

Calabar Python,

rather than "Calabar Boa". A common name is just that - a name

that

is commonly used by many people. The common name certainly may

change

over time, but at this moment it remains the same and there is no

reason to

change it.

Natural history: The Calabar Python is found in West Africa inhabiting areas of moist soil in forest environments. It is a tubular snake with blunt tail and head. It is generally described as a burrowing animal that preys on lizards and small rodents. The method of defense employed by Calabars involves rolling up into a tight ball with its head in the center and the tail exposed. The head is relatively featureless and if you are any distance from it, you quickly discover that it is virtually indistinguishable from the tail. The eyes are small and the same brown color as the scales surrounding it; the mouth is not a visually distinct structure. There is no apparent neck in the adults and the shape of the tail is identical to the head. As an added "attractant" for the tail, almost all of these animals have random patches of white there that may serve to draw attention to that part of the exposed "ball". At one time I believed that these white patches were found in all specimens, but I recently obtained a female that lacks any. The balling defense has been used by all of the snakes I have kept, and there has never been the slightest sign of an intention to bite. Wild caught animals reach a maximum of 3+ feet but it will be interesting to determine the size that captive born animals eventually reach. The adults that I have seen are all patterned with brown and yellow scales. Neonates have a reddish color rather than the yellow for about 1 year, after which, the reddish scales gradually fade to yellow. I have recently been shown pictures of a WC adult that retained the reddish color. These are not as common as the brown animals and whether they represent regional color morphs or simple variants is unknown.

Husbandry: The following information is

derived

from my experience with three long-term wild caught (WC) animals and a

CB neonate added several years ago. The animals were all kept in one 20-gallon

aquarium with a screen top. Using wood and Plexiglas squares as

platforms, I have made the cage tiered. There is a heating pad

under one end of the cage although the animals are never at that spot

except in the days immediately following feeding.

I use paper to line the bottom of the cage. A large, stable,

water dish

is kept in a corner. The animals are kept in a room where the

temperature

remains approximately 75-80° F throughout the year. These conditions appear to be satisfactory and there have

no

problems with disease or refusal to eat I noted, they appear to prefer the cooler

area. As noted below, however, there may be a requirement for a warmer area when animals are gravid. I have

never

cooled the animals down and they have continued to eat during the

entire

year. Many people also recommend keeping the humidity high. I do not do

this

and have not seen any problems with shedding, although the sheds come

off

in several pieces. In all the years that I have kept these

animals,

retained eye caps have occurred only once and were removed with the

subsequent

shed. I feed live or frozen/thawed rodents - no larger than mouse

"fuzzies"

and have never had any problems with the animals eating. I do not

give

them mice old enough to have open eyes. The Calabars are almost

lizard-like

in their feeding - that is, they do not gape their mouths as wide as

many

other

snake species do. They are deliberate feeders and initiate eating

by

"probing" the feeder pups rather than striking. They compress the

food

within their coils and against the sides and floors of the cage.

Their "personalities" and habits are

quite

interesting and lead to some unusual aspects in their husbandry.

They

are prodigious eaters and the 20-25 large fuzzies given per feeding to

the

trio (generally once a week) are invariably gone the next

morning.

Often, this is the result of one snake eating most of the food.

The

next week another snake(s) will do the same and there has been no

trouble

in maintaining the animals in a single cage. The only time they

refuse

food is during the late pre-shed period (they turn a milky blue gray at

this

point) and one or two days before egg laying (although one female ate

some

fuzzies on the morning of the day that she laid three eggs).

Their

weight fluctuates between feedings to a much greater extent than any

other

species I have kept. The intake of water is "record

breaking"

for their size. The water dish has to be constantly refilled and

I

often see them drinking. While they are supposed to primarily be

a

burrowing species, they are seen prowling during the day more often

than

any of the other species I maintain, especially when they are hungry.

Breeding and egg

incubation:

First, a quick note on the sexing of this species. Probing is, of

course, one method and Ross and Marzac list the probe depths of the

sexes as 10-11 scales in the male, and 3 scales in the females.

It would appear that probing is not necessary, however, since only the

males have noticeable spurs lateral to the anal scale.

My original pair of Calabars has

successfully

bred for the last eight years and a newly acquired female bred the

first

year that she was in the group cage. I would like to take credit

for

having come up with clever strategies to allow breeding, but the first

clutch

was a complete surprise. Since then, the animal has produced

clutches

every year. I have observed these animals mating at different

times during the last three years. Mating took place during a

considerable range of months; October in 2004, and September through

November during 2005. Observations were always made when I turned

the lights on some hours after the room had been completely dark:

I happened upon this scene while checking on my animals in the evening

after the lights were out in the snake room. Soon after I took

the picture, they had separated and went back into the hide area below.

The female laid eggs three to five months after

mating.

As the eggs develop internally, the female becomes

swollen

in the posterior third of the body.

When

this becomes noticeable (see immediately below), I transfer it

to a

10 gallon aquarium with a nesting box containing moist potting soil,

and an under cage heater to provide more warmth.

Male (above) and gravid female (1-26-03). Three eggs were laid 17

days

after

this picture was taken.

Another sign of gravidity is that the areas between the scales in the abdomen become readily visible:

Gravid female on the left (four eggs laid 45 days after picture); male

at

right.

Calabar eggs are extremely large in relation to the size of the adult

female:

These are a series of questions that

I

have about the behavior of some of the snakes in the collection.

I

don't have any definitive answers for them, just ideas. If you

know

of references to material that may offer solutions or if you have any

comments,

let me know...

1. Reason for non-breeding in WC animals.

I have successfully bred Calabar pythons - A wild caught (WC) male and

female

purchased in 1993 and 1994 respectively. I housed them together

and

did nothing other than feed them regularly and offer large and

necessary

amounts of drinking water (details of care for this species are found

above).

In 1998, the female became gravid and laid a clutch of normal

eggs.

Every year since then, she has laid eggs. I assumed that

the

four years between her arrival and the first clutch involved

acclimation to

the point where breeding could occur. I also assumed that this

acclimation

was most important for the female for the following two reasons.

The

first is that the production of eggs involves a great expenditure of

energy

(the clutches have been in the range of 30-40% of the female's

pre-laying

weight). It therefore stands to reason that the stress of a novel

environment

would inhibit the female reproductive processes more than the male who

only

has to expend the energy required for a few ejaculates. The

second

reason is rooted in male chauvinism - it's the female who always gets

the

"headache" while the male is raring to go… A friend purchased

a WC female two years ago. On a whim, we placed it in with my

pair.

Our only concern was that the presence of the new female might inhibit

the

breeding of my pair. We were very surprised when both females

laid

clutches of eggs within one day of each other. Is it therefore

possible

that the male is more reluctant to breed in a novel environment than

the

female? The new female had to be receptive and she was in the USA

less

than a year before laying a clutch. Perhaps, at least for some

species,

it is the male that fails to breed rather than a "non receptive"

female.

The question, then, is whether the above assumption is correct, and if

so,

is it true for other species.

On this topic, I would note that

based

on our original assumption, we placed some male Mandarin Rat Snakes

that

were WC in 1999 in with a captive bred female of sufficient size and

age

to breed. The animals showed no signs of breeding and the female

did not become gravid.

2. Question re: yolk formation in non-gravid

females.

Some years ago my viper boa gave birth to a large litter (23).

This

is another species that is rarely bred, and my

breeding

strategy was similar to the Calabars - put a male and female together

and

leave them alone. She never bred again

and subsequently

the male died. The following year after the male died, she

proceeded

to gain weight as she did when she was gravid -

this

species resembles a Gaboon Viper in being short (1 1/2 - 2 feet) and

attaining

a huge girth that virtually prevents it from

coiling.

I was curious about the weight gain since there have

been a fair number of reports of snakes apparently retaining sperm (or

more

likely, fertilized ova) across seasons and then

giving

birth in the absence of subsequent contact with a male. She

attained

a weight of over 1 kg, and then stopped eating

and

began to lose weight. Around this time I noticed small, hard, brown matter in the bedding. I assumed that it

was

dried feces and simply cleaned the cage. One day, I noted that three large egg masses - that is, yolk

material

floating in the water dish, and I realized that

the

brown material was dried yolk. This past year, the identical

thing

happened with a Rainbow Boa kept by a friend and again, masses of yolk

were

deposited in the water dish. This type of event raises a number

of

questions: Why does an ovoviviparous animal

pass quantities

of yolk rather than conserving energy by re-absorption? Does this

ever

occur in the wild or is this phenomenon simply a result of excellent

availability

of food? How common is this phenomenon in

captive

animals?

3. What are "slugs" (infertile eggs).

Snakes sometimes lay slugs. These are soft,

thin

walled "slippery" eggs that succumb to fungus very rapidly. The

only

reference to this phenomenon that I have found is a single note

referring

to them as infertile. I very much doubt that there is any hard

evidence

for this - just an assumption that since the eggs never produce

hatchlings,

they must be infertile. If this assumption is correct, I wonder

what

the mechanism would be that "signals" the female not to bother

depositing

a normal (thick) layer of calcium on the exterior of the egg. It

would

have to be a signal that regulates shell formation and relies on

fertility

as the trigger. The developmental stage of corn snake and ball

python embryos at the time of laying appears to be somewhat similar to

a 48-72 hour

chick embryo. While in the mother, therefore, the embryo is very

small

and immature. How would such an embryo produce enough "signal" to

affect

shell deposition? An equally (or more) attractive hypothesis

would

be that the slugs are fertilized eggs that are laid prematurely,

possibly

as a result of stress. My black milk snake (Lampropeltis

triangulum

gaigiae) female once produced 12 full-size slugs. She mated

with

the male on numerous occasions, so unless one of the pair is infertile,

the

eggs were fertilized. Why then, did she lay these slugs? In

retrospect,

I may not have provided an adequate nesting box. Could this

factor

(and possibly others) have induced stress that was involved in the

production

of slugs? If stress is a factor, there is again the problem of

signals.

In this case, however, one could postulate hormonal imbalance induced

by

stress chemicals.

4. The

question of double clutches.

A number of snake species "double clutch" - that is,

they

lay an initial clutch of eggs, and then after a suitable interval, they

lay

another clutch (no male being introduced between laying). Very

often

(in my collection anyway) the second clutch is not nearly as viable as

the

first - many slugs and few viable eggs. My anerythristic corn

snake

laid 20+ viable eggs and then followed with a second clutch of 10 slugs

and

one thin-shelled egg. What is the mechanism of double

clutching?

I would assume that fertilized (or unfertilized) ova are in some sort

of metabolic

and developmental stasis. Is this phenomena dependent upon

abundant

food between the clutches? Is this something that only happens in

captivity

- in fact, has it been bred into captive animals the same way that we

have

bred chickens that lay an egg(s) every day?

5. Fecundity issues.

I worked with a group of 11 Mexican Milksnakes (Lampropeltis

triangulum annulata). I bred the eight females with the three

males

in an ordered fashion. I waited two or three days before using

the

males after a previous breeding. All females were bred 3 or 4

times.

In all instances, copulation was observed. The end results were:

one

snake laid slugs; one snake laid slugs and viable eggs; one snake laid

eight

viable eggs; and five snakes never showed signs of being gravid.

The

question I have concerns the "whys" of non laying. Are the males

incapable

of breeding as often as we thought they would be? Are the females

differing

in their fertility? The statement "proven breeders" appears on

commercial

lists of snakes for sale. I wonder if this is an indication that

the

successful breeding of these animals may be less common than I thought.

6. Mating behavior.

When some male and female snakes are put together

for

breeding, there is a characteristic twitching on the part of the males

(and

to a lesser extent, the females). This behavior occurs in all of

the

Colubrid species I have observed. What is the reason for this

twitching?

It is the only time that I have observed this behavior. I can

find

nothing in the literature concerning this phenomenon except for simple

description.

This does not occur before or after the breeding season. It may

not occur when two males are put together during breeding season.

In the

case of two male Honduran Milk Snakes (Lampropeltis triangulum

hondurensis),

in cages adjacent to a receptive female, they simply bit each other

when

placed in the same cage.

7. Temporary color change in adult

Calabars.

On November 27, 2002 I weighed and examined my

Calabars

as part of my husbandry routine. At that time, they all appeared

to

have normal coloration. On December 13 I examined the animals and

noted

that the female F1 was in the midst of shedding and seemed to have

developed

a striking color change in the dorsal scales of the first third of her

body

as well as some white scales on the top of the head (see picture on

left

immediately below). I assisted her in shedding and it became

apparent

that the color change was not the result of retained shed - areas that

I

helped remove the shed from had little discoloration, while the major

areas

of discoloration had not retained the shed. Six weeks later (Jan.

16),

the discoloration was still present although greatly reduced (see

picture

on right immediately below). There were no signs of additional

shedding

in the areas that had lightened. The behavior of the animal

appeared

normal and there was no loss of weight. At the time of the second

picture,

the animal was gravid and she laid three eggs on February 12. She

ate

approximately 20 fuzzies on February 13, and in terms of behavior,

appeared

to be perfectly normal. Neither of the other two Calabars (1.1)

in

the same cage showed any sign of color alteration. By March, she

had lost all signs of the color change. The questions are obvious: What

is the nature of a color change with such a rapid onset, and what

induced it.

12-13-02

1-16-03

TENTATIVE ANSWERS:

As a scientist I know that solving biological problems is not a simple process of finding the one absolutely correct solution to the problem at hand. Based on the evidence I have gathered to date, however, the following are tentative answers to two questions originally asked above. Like every answer in science, it remains open to changes resulting from new information and/or observations. But for now, the evidence indicates the conclusions given below:

Viper Boa:

1997

Animals were observed copulating in water once during

April.

Female gave birth Oct. 11. There were 23 live and 2 dead.

Birth

was not observed.

Attempts to feed with pinkies, unscented pinkies,

and

pinkies scented with salamander slime were unsuccessful. A small

number of animals did eat pinkies scented with a leopard frog.

The neonates were maintained in small containers partly filled with wet

sphagnum moss

and a dry area. The animals appeared to have remained exclusively

in the moss. All non-eating neonates were force-fed with

macerated pinkies

through a syringe. The response to this strategy was strange in

that

the neonates lost most of the intubated weight between feeding (at one

week

intervals). In the end, only 2 neonates survived.

Calabar Python

The Calabar in 2000 with her clutch of three eggs.

2003

2/12 - F1 laid 3 eggs in nesting box. Eggs placed

in

incubator at 84° and 90% humidity.

3/31 - F2 laid 4 eggs in nesting box. Eggs placed

in

incubator at 82° and 90% humidity.

4/8 - F1 clutch: (d55) I slit the two flaccid eggs on

top

with an approximately 1cm cut. There was no leakage of yolk.

4/11 - Hatchlings pipped in the egg that had not been

slit

and one of the slit eggs. There was movement in the other egg.

4/12 - Neonate emerged from "non-slit" egg and placed

in

cage (wt. 36.6g); third hatchling pipped.

4/14 - Remaining two neonates emerged from eggs and

placed

in cages. The weights were 39.4 and 37.7g.

5/6 - Discarded egg that was shriveled and had mold growing on

it.

It was the uppermost egg and had collapsed to a greater degree than the

other

eggs.

5/16 - Two eggs slit - movement was detected in both

eggs.

5/18-19 - Neonates emerged.

Neonates did not begin to eat until 3-4 weeks after

hatching.

Rainbow Boa:

2001-20022004-5

Animals observed mating but female has shown no sign of

gravidity. Female eventually "gave birth" to a series of slugs

and

one partially formed embryo.

2000

4/8-4/25 - Animals bred.

6/23 - F4 laid 13 eggs.

7/2 - F1 laid 8 eggs.

Gray Banded Kingsnake:

20002003

4/26-5/21 - successful matings.

7/20 - Laid 4 eggs, 1 good(?), 3 slugs.

8/6 - Laid 4 eggs, 2 good, 2 slugs.

Eggs incubated at 82º, 96%

humidity.

The eggs were not viable.

Mexican Milk Snake:

19992002

4/24; 4/26; 4/27 – Animals mated.

8/2 - Laid 1 egg.

During the second week of August it became apparent

that

she was egg bound. Palpation did not move the eggs and in late

August

she was given to a veterinarian who surgically removed the (6)

remaining

eggs.

10/4 - Normal neonate found hatched.

Black Milk Snake:

2000Sinaloan Milk Snake:

1998

Animals bred on the following days - 3/15; 3/21; 3/28;

3/29;

4/26; 4/30; 5/8-9; 5/12; and 5/15. Activity was

intermittent.

Positive mating occurred on 4/30.

Female ate at various times through 7/3.

7/20-21 - 10 eggs laid in nesting box that contained

sphagnum

moss and peat moss (relatively dry).

7/22 - Eggs weighed 123.5g (female weighed

÷

344.5g). Eggs 36% of pre-laying body weight.

7/27 - Eggs weighed 123.8g. Those on top were

collapsed

to some extent.

7/29 - Eggs weighed 125.0g. Eggs appeared

unchanged.

7/31 - 126.0

8/18 - Eggs appeared unchanged.

9/10 - 146.7

9/17 - Hatching begins (59 days): 4 snakes pipped

9/18 - 3 snakes out of egg

9/19 A.M. - A total of 7 snakes out of egg. 2

pipped.

1 egg (uppermost one) slit with razor. This egg is full, movement

detected.

9/19 P.M. - 2 pipped snakes in morning left eggs.

9/21 - Pinkies given to all 9 snakes.

9/22 - 4 snakes ate

9/23 - Remaining egg slit by snake (away from slit that

I

placed in egg)

1999

Male removed from brumination on 3/19

Animals bred on the following days - 4/18; 4/23; 4/30;

5/4;

5/195/27; 6/6; 6/12; and 6/18. Activity was intermittent.

Positive

mating occurred on 5/27, 6/6, and possibly 6/11.

Female ate at various times through 6/14.

7/1 - 8 eggs laid in nesting box that contained peat

moss

(relatively dry).

8/26-29 - 7 eggs hatched (57-60 days)

Mountain Kingsnake:

20002004

3/19-4/30 - Similar experiences as that of 2003.

2005

The female escaped from her cage during November, 2004 and reappeared

in March, 2005. She appeared to be in good condition although

obviously thirsty. Normally, she begins eating in June, but this

year, her "emergence from brumination" has been delayed and she has

eaten only sporadically through the month. Nevertheless...

6/23 - Female placed with male. Male showed twitching behavior

and attempted to track female.

2004

3/19-4/1 - Animals placed together, male twitched occasionally, female

showed

no interest. Not surprisingly, no eggs were laid.

2005

2/7 - Female placed in cage with male. There did not appear to be

any interest shown by either animal towards the other at any point

after that. A friend and I were, in fact, wondering if we had a

pair, and had decided to have the animals probed. Then...

6/22 - 5 eggs were discovered in cage(!). The eggs were somewhat

collapsed and one has a yellow color and appears to be

non-viable. The eggs were all placed on moist vermiculite in a

covered glass bowl to ensure maximum humidity. A week after

laying, the eggs seem to have filled out somewhat and there is no sign

of fungus.

7/15 - 2 eggs were discarded as they were collapsed and clearly

non-viable. The two eggs were the yellowish one and the one that

was initially the most collapsed. The remaining three eggs were

fully filled out, white, and apparently viable.

8/12 - All three eggs had hatched and the neonates appeared to be

healthy. 2 neonates ate (live pinkies) after first shed.

The third neonate was force-fed Gerber's Beef Baby Food in 1ml amounts

with no problems and there was some weight gain. It refused

food and eventually died.

2006

5/30-6/10 - 5 eggs laid on different days. Only 1 egg appeared to

be normal, all of the others were slugs. Three had been discarded

by 6/15 and one soft shelled egg was kept since no fungus had appeared

as yet. The female did not appear to be done laying (her ventrum

was not "hollow") and I left her in a 10 gal. aquarium with a nesting

box. Soft shelled egg was subsequently discarded.

7/25 - Egg hatched, neonate found in incubator.

8/10 - Neonate refused food, died. My assumption is that it was

not normal at hatching.

2007

No activity noted and no eggs laid.

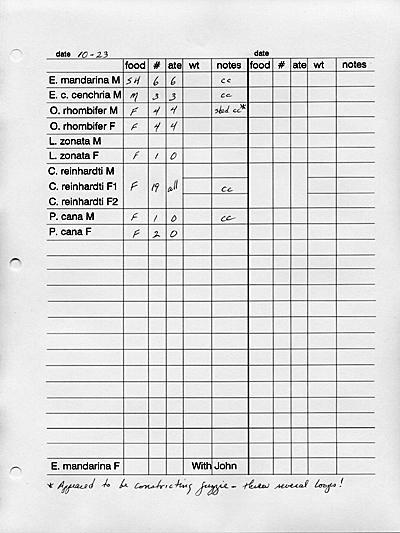

RECORD KEEPING:

It contains feeding data, shedding information,

weights, and a note

describing an observation made on one of the animals. I store the

data in standard 3-ring notebooks and the format can easily be changed

to reflect changes in the collection.